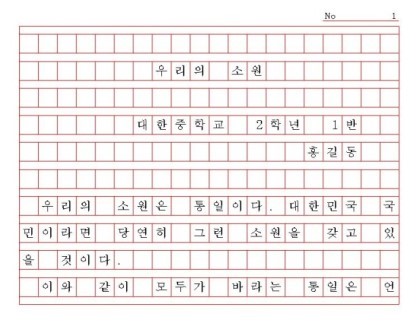

Using computers was pretty common and obvious when I was young, but I was in the transitional period that certain handwritten system also existed in Korea. It was writing on a given form, a ‘squared manuscript paper’. The most general type was for 200 characters with red lines. Each square can contain one letter, one mark, or one space. Elementary school essentially educated how to write on the squared manuscript paper in class, and official writing assignments and tests were to be written on it. At the same time, however, I was technically accessible to the word processor and knew how to use it. That is, I was a generation that was able to experience both forms of writing.

As with all handwritten system, writing on the squared manuscript paper has the tension of the uncorrectable. The difference is that it has the precise rules, even for which signs to use when making corrections (of course, in this case they are intuitive and universal, but still definite to follow). In this format, the actual writing had to begin very deliberately after careful consideration of the entire content of the writing. On the other hand, writing in a word processor made it more improvised and showed that the flow of thought can be cut and edited in a visible way.

Having many strict forms means it has authority. The ways to write on the squared manuscript paper were to be learned and trained. How well someone follows the format correctly, how well someone writes a complete composition with one stroke of a brush, or whether someone knows the rules when he/she has to modify it; these are a glimpse of the writer’s level of education. Indeed, writing on the squared manuscript paper was a symbol, especially of an intellectual. Despite the fact that word processing is now perfectly generalized, many contests of research or composition in Korea still announce the length limit of the writing based on the form of squared manuscript paper. Does the development in technology of writing equalize all of us and allow anyone to express their thoughts freely? A few years ago, I made and edited a book of stories that were created by long-time local residents, setting up the town they live as a stage of the stories, as part of activity against gentrification. The most enthusiastic, middle-aged male participant who had a dream of novelist but couldn’t realize it, and now run a small fried chicken restaurant, visited to give a handwritten composition on the squared manuscript paper when all other young participants e-mailed a word processor writing. Ashamed of the fact that he had never learned to use a computer, my team moved dozens of his handwritings to Word. Technological advances have made my writing fast, efficient, able to write anytime and revise whenever I want to, but is it really freeing everyone, including me? Are we perhaps isolating another invisible class in our writing technologies and composition process?