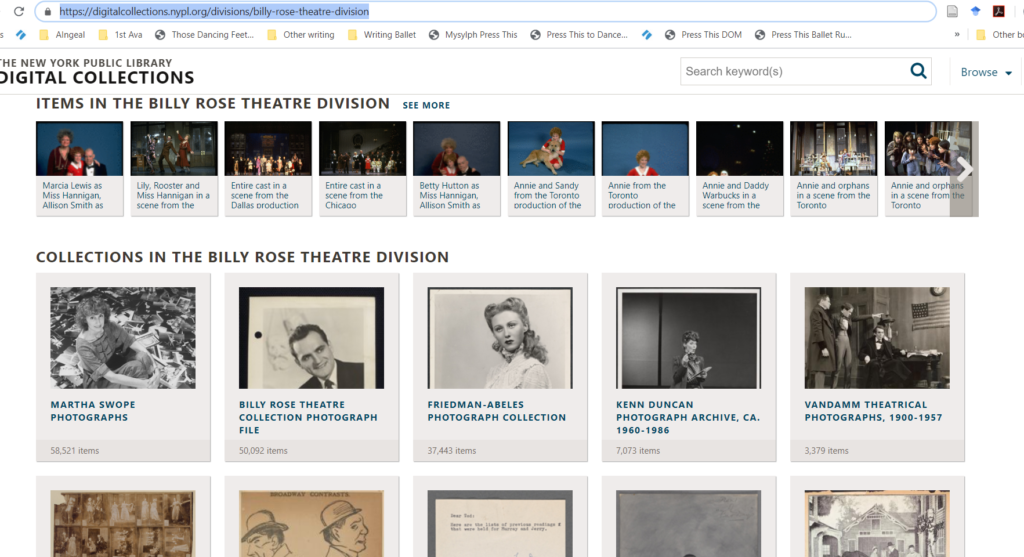

NYPL/New York Public Library of Performing Arts-Billy Rose Theatre Division

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/divisions/billy-rose-theatre-division

The New York Public Library’s Billy Rose Theatre Division is one of the world’s largest and most extensive archives of the theatre arts. It is located at The New York Public Library (NYPL) for the Performing Arts (LPA). The division’s special strength is American and European performance in the 19th and 20th centuries including:

Archival collections https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/divisions/billy-rose-theatre-division

Books and Periodicals

Clippings and Reviews

Photographs

Programs

Scrapbooks

Scripts and prompt books

Set, costume, and lighting designs and other production materials

Posters, window cards, and other visual material

Rare books

Theatre on Film and Tape Archives (TOFT)

From producing live theatre recordings to the collecting of personal papers and ephemera, the division boasts more than 10 million items documenting drama, musical theatre, film, television, and radio, from the Renaissance to the present day. Not all items of the division are digitized, but to date 800,000 items are represented online or provided as links with directions to viewing the personal objects. Due to the size and complexity of the NYPL and the wealth of resources it attracts from individuals, it has taken over one-hundred years of archiving and organizing skills to develop, maintain, and digitize the collections to date, and it grows each year with new acquisitions and donations. For a comprehensive list of Theatre Division clippings, photos, programs, reviews, and scrapbooks, you will have to visit LPA’s third floor and search the freestanding card catalogs, but a fair sampling is available online. No thorough research of any subject or topic could be said to be complete with only an online search of the materials there, but as far as standards are concerned, the NYPL is a frontrunner regarding the classification of materials, and many online archives follow their examples and system. Some classifications are Dewey Decimal system ones, and others are their own (writer them down, don’t bother trying to figure them out). Like all libraries, recording all associated and catalog numbers, as well as noting locations, are essential for tracking down any objects.

While online you can see much of what’s available in NYPL’s online Classic Catalog. https://catalog.nypl.org/search/ Here you can do a keyword, author, title, or subject searches. There is an Advanced Search tool on the left-hand side where you can search, multiply or individually, by title, author, subject, etc. With library membership, it is easy to register, search in different ways, and save searches. This is an invaluable aspect for researchers. Also, library assistance is only a call, an email, or a visit away.

In the case of manuscript collections, or among the papers of individual artists, records of theatre companies, producers, and related companies-the Archival Materials search page allows you to do keyword searches within NYPL’s “digitized finding aids,” and bring different results from the regular catalog search. Finding aids provide detailed information on the subject of individual collections, such as biographies, lists of the collection’s contents, and other relevant research information. It is important to remember that the items you are researching are actual items in a box or a folder and usually information, from manual cataloguing is written on the back, or they are tagged. Only an actual visit to see the physical items at the library will produce comprehensive results. http://archives.nypl.org/ Therefore, the Archival Materials search will also link to the catalog record, and the information you will need in order to find out where a box is stored. You will need both the finding aid and the catalog record to accomplish this.

Recently the library launched a website https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ to access and engage with all of its currently digitized content, both at the NYPL, within its divisions and collections, and as provided by outside partners including Hathitrust, and others, making it easier to find additional material, and the collections themselves. This site is updated everyday and is especially useful for keeping up to date on recently added items. Broadway.com also liaisons with the library concerning theatrical materials and records and posts regular articles by appropriate personnel about new acquisitions, feature artists, and background material. One can sign up for alerts there as well.

If you are looking for a published play-the Billy Rose Theatre Division does not collect published plays, only scripts and promptbooks-check the Drama Desk. Most of the scripts and promptbooks are listed in the card catalog, but older scripts are available on digitized card catalog records here https://s3.amazonaws.com/cardimages.nypl.org/index.html

If materials are located elsewhere it will be noted in the catalog record under their location, but for specific information or to request offsite LPA materials go here https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/lpa/requesting-archival-materials

One example of a collection which has theatre holdings related to LPA, but not stored at LPA is The Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture. https://www.nypl.org/locations/schomburg Physical sites, such as these might have related materials to your research by name, topic, etc.

The NYPL has been collecting theatre materials prior to 1931, when the executors of David Belasco’s estate offered his holdings on condition that a collection be created. Foremerly known as the Theatre Collection (Sept., 1931-), it was renamed the Billy Rose Theatre Division https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/divisions/billy-rose-theatre-division, retaining its location. The Billy Rose Division is now the largest research division at the NYPL.

The Theatre on Film and Tape Archive (TOFT), which produces video recordings of New York theatre productions, is a groundbreaking enterprise begun in 1969 by Betty Corwin. Due to her energetic research and union agreements, over 7,901 titles have preserved, including interviews, ethnic and minority productions, oral histories, and the work of specific playwright’s. Screenings limited to students and researchers are available. Between 50-60 live recordings are produced each year, covering most important productions. Copying is not permitted. https://www.nypl.org/about/divisions/theatre-film-and-tape-archive

To directly access the holdings of The Billy Rose Theatre Division, organized by its collections, visit https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/divisions/billy-rose-theatre-division or view related collections with icons to direct links here https://www.nypl.org/locations/lpa

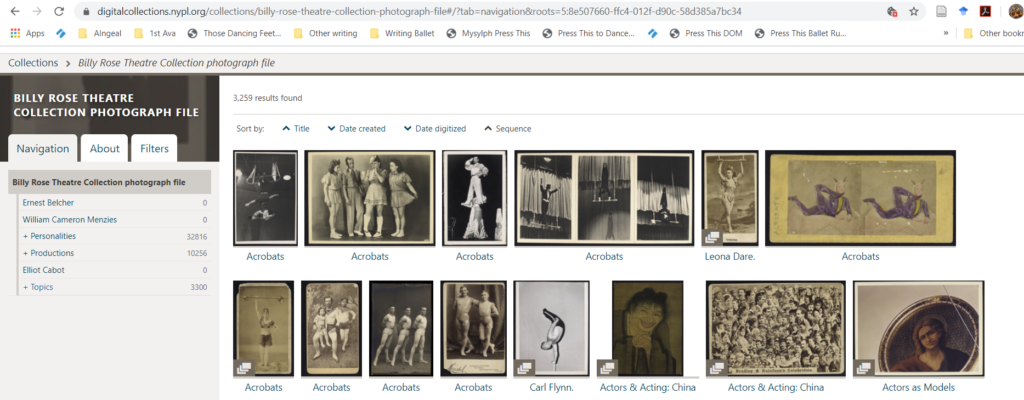

Browse or click on one of the collections to view holdings.

Doing a filtered search will give various options and the number of individual records is listed beside the heading. It is possible to refine searches and to cross search this way among the different collections. Larger collection containers will appear first and those with fewer items will appear later.

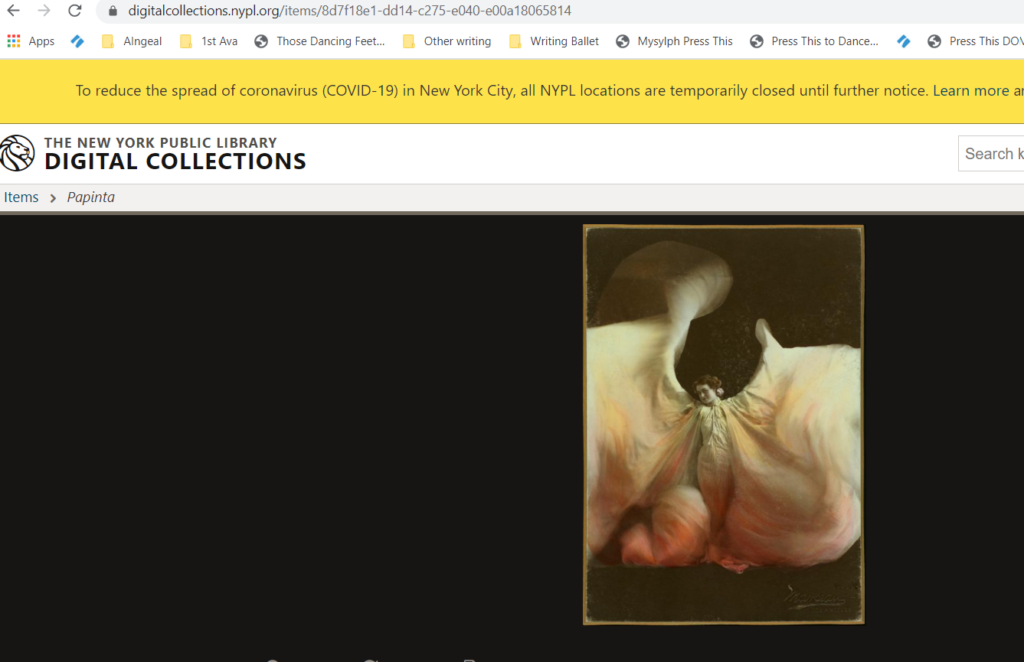

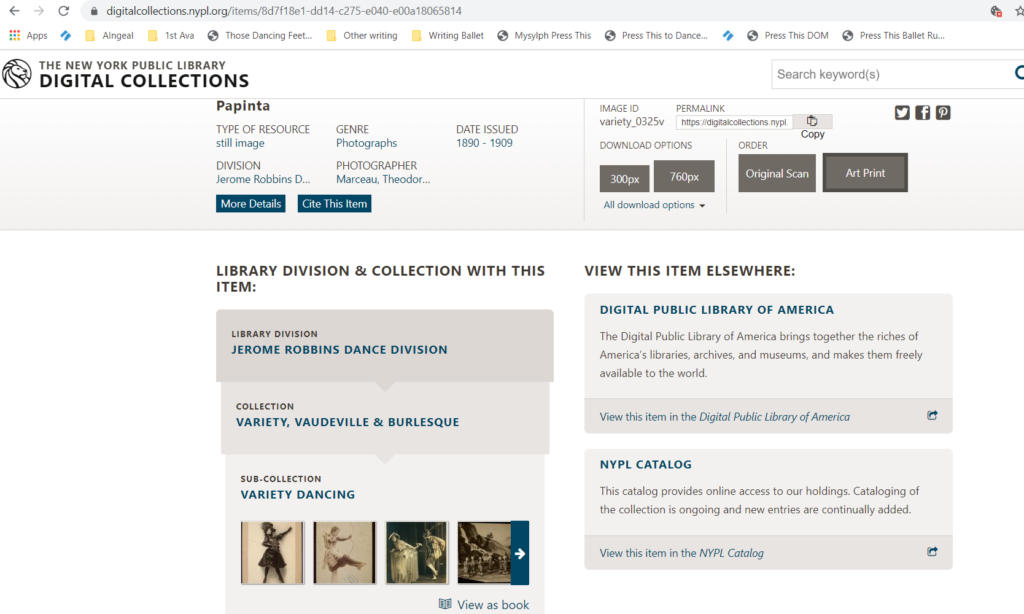

Click on the item for details. You can zoom and print.

Scroll down for more information and to view the hierarchy, container, and sub-collection results, where else to view the photo, etc. Note the photos within that group/collection can be viewed as a book, which is particularly helpful if you do not want to click on every item in the group search results.

Also note some items in the group will sometimes (usually not) be cross-referenced in other Divisions, such as Jerome Robbins Dance Division, if applicable.

Under More Details, Item Data and how to Cite this item are available.

Searching within the collections is much easier than a broader search, but it is easy to assume that more records and items are not available-you have to do a wider search and include more divisions. This is possible using the directions above.

To search within the collection itself, click on the collection icon and all of its holdings will pop up. If this number does not match the folder number, it is because more items from different collections are being included. I haven’t determined exactly why this happens yet, but I think it has to do with the exact folder the item is in and the fact that it is cross-referenced somewhere else. It does not contain all those items in the result here, but viewing the item itself will bring the additional items in that folder up. At least that is one theory.

Search filters and information are on the left-sometimes pertinent biographical information of the collector is available by this method in the About area. In The Billy Rose Theatre Photograph Collection, there are 50,092 items, but by using various filters more, or fewer, items are grouped together.

Contents, as well as additional search filters, are listed on the left. The largest categories are listed as well as 3,300 additional topics. The topics are also listed underneath the photos, so that if you see one that interests you, you can click on it. Other photos in that group will be available at the bottom of the page once you click on it.

Under Filters, additional options are available. I can search through the “Navigation: Productions” photos for pictures of dancers, or I can search in “Filter: dancer” for different results.

Note, also, the different numbers of the results for the containers searched.

I have found the Divisions of the NYPL/LPA very useful for researching performing arts in New York, although there are other very useful resources for my subjects of interest, i.e., dance/ballet. It is one of the easier websites/archives to use, although different and repeated searches are necessary to find items sometimes-this can get confusing due to jumping back and forth. Remember to save your searches, to make records/take screen shots.

There are some glitches with the system I have found, particularly in the failure to cross-reference material, and the lack of information available on some NY-based artists/producers who are underrepresented, or not represented at all here. However, overall, they are accurately archived, and their holdings are just about the largest I have encountered related to theatre arts in the country, with exception of the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress (for some material), and it is easy to use for research.

The advantages of their cross-referencing, and the ability to cross-search across the divisions and collections is superior to any other searchable archive, bar none, although that is not wholly addressed in this review. I have included a great deal of information regarding the structure of the catalog system at NYPL because it is so important to research in the performing arts to be able to search across divisions for possible literary, business, and other categories which the keywords will produce results.

Examples of frustrated searches limited to the Billy Rose Collection include few references of actor/dancers, such as James Cagney, businessman and philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein, and no results for theatrical manager, author, and publisher Elisabeth Marbury or her friend and roommate, Elsie de Wolfe. However, a broader search of the Digital Collections/Digital Gallery produced Lincoln Kirstein (173): https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/search/index?utf8=%E2%9C%93&keywords=lincoln+kirstein

James Cagney (21): https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/search/index?utf8=%E2%9C%93&keywords=james+cagney

Elisabeth Marbury (18): https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/search/index?utf8=%E2%9C%93&keywords=marbury

And Elsie de Wolfe ( 11):

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/search/index?utf8=%E2%9C%93&keywords=Elsie+de+Wolfe

From there, you can expand even further-the broader the search, the more results are going to appear over the whole of the library’s holdings, other divisions, locations, etc., and it is essential to visit the Billy Rose and other Divisions of the LPA personally as the card catalogs are an invaluable resource. It is clear from the number of results, in contrast to the vast record of holdings, that about only 1/10 of the items are digitized to date.

Citations

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Papinta” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1890 – 1909. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/8d7f18e1-dd14-c275-e040-e00a18065814

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Valentina Kozlova (Vera Barnova replacement) and Leonid Kozlov (Konstantine Morrosine replacement) in the 1983-1984 revival of On Your Toes” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1984. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7b7e0625-6b49-5b28-e040-e00a18061238

Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. “Agnes De Mille (director and choreographer) in rehearsal with dancers in Allegro” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1947. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7ae01264-7aa8-2cdf-e040-e00a180632a0

Billy Rose Collection, Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library

Creator: Billy Rose, 1899-1966

Call Number: 8-MWEZ+n.c. 26.288-26.293