Concluding with the documentary The Machine that Made Us, I found Stephen Fry’s final thoughts on print and the modern age quite perplexing; it was how he could not perceive modern society without the printed word. I find that I agree with this notion, but in a different manner: I instead see that the book and society have and still continuously shape each other. While an idea as text can die as pure intention in the mind of the author, the book must take on the weight of society in order to navigate the processes of transmission. At the other end of the spectrum, society can foster books as “building blocks of civilization” in order to construct itself and its collective consciousness.

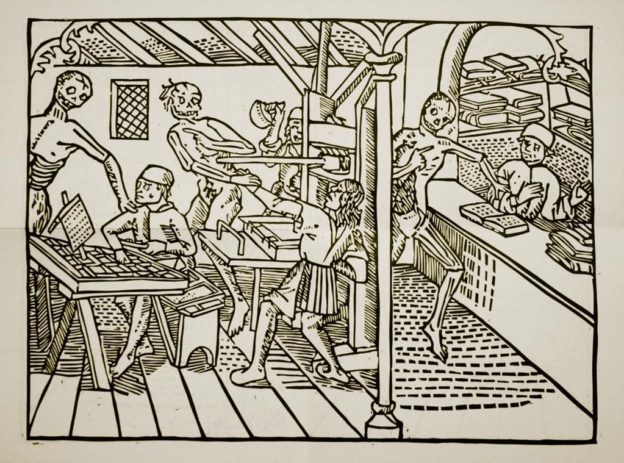

But while Gutenberg’s printing press universalized text and its ideas, the book in its respect to society can also be at its mercy. What I found especially interesting was just how much the process of textual transmission is social and the extent to which it is affected economically, politically and culturally (which Sarah Werner reflects upon in her final remarks). While I see that the book and reading have made bounds in terms of accessibility, the fact remains that the book’s physicality limits the terms of its distribution and development. As Abbott & Williams ascertain, the text is inherently tied to history, its makers and its circumstances.

Similarly, the ascription of value by society is reflected in the analysis of the process of print. Just as printing was and is a process of transmission, so is reading within and out of the context of printing. As I and others read, we unconsciously enact our values on books and the way we funnel their information. Alterations and versions of a book through active participants in the publication process showcase this and perpetuate how the distinction between author and reader can blur (reference Abbott & Williams intricate “text to” web diagrams).

I find then that the most we can draw from the history of print is has and still provides a network of interpretation, showcasing that text in its transmission to the format of books will always be subject to change. What has newly developed however is a breakdown of what dictates value as it becomes more decentralized in the advent of the digital age. It is the unanticipated extent of radicalization to tradition then that I believe print and later processes of distribution invited to society’s relationship to books, especially reading and the context with which we now view history. How this has and will affect us though will continue to evolve over time, remaining as fluid and subject to change as society is.