The William Blake Digital Archive:

The William Blake Archive sets out to compartmentalize and make easily accessible the wide variety of material under its collections central figure, William Blake. As a poet, painter and printmaker, the site makes use on the home screen of visual imagery, remediating in its interface a randomized assortment of Blake’s paintings to scratch the surface of his artistic range. The project’s most apparent ambition is managing to encapsulate the multi-faceted pursuits and characterizations of Blake and translate that in a more easily digestible format.

Biography:

http://www.blakearchive.org/exhibit/biography

The unique and interactive biographical “exhibition” by Denise Vultee for background context is one that again utilizes visual imagery alongside an essay (text) rife with citation in the form of footnotes with attached images. Combining the consideration of the writer in their use of citation (the least amount of interruption for maximum textual engagement) along with remediation and the reinvention of the essays, the split screen format of William Blake’s biographical information reimagines the exhibition in a digital platform unlike that of online museum catalogues. I found that I was able to immerse myself especially with the journey through outlined periods in his career that transitioned and bled into one another rather than being separately distinguished or isolated through compartmentalization.

Summed up through the quotation, “Blake’s creative activities were not confined …. during these years”, the site consolidates this concept throughout its digital environment. One such important highlight is how his endeavors, particularly in his work on illuminated printing and illustrated books, constantly exposed him to various ideologies and more politically driven authors and works whose intentions coincided with slavery, poverty and various other radical issues in the late 18th and early 19th centuries; all of which, he would later integrate into his own Classical-centric body of work. The same format applies to the archive’s other reworked exhibitions, which demonstrate the same intention of simultaneous gallery and essay cooperation—elaborating more on Blake’s venture through the technical aspects of the engraving process (“Illuminated Painting by Joseph Viscomi”) and a case study on Blake’s engraving and painting of the Canterbury Pilgrims (“William Blake’s Canterbury Pilgrims”).

“William Blake’s Canterbury Pilgrims”:

http://www.blakearchive.org/exhibit/canterburypilgrims

The archival exhibition, “William Blake’s Canterbury Pilgrims”, uniquely chronicles Canterbury Pilgrims while positing the concept of originality and ownership, offering rival contention and comparison between Blake’s rendition and Thomas Stodhard’s The Pilgrimage to Canterbury, each of whom attempt to fully claim authorship of the scene and its iconography. This includes organized lists of hyperlinks that interject the text labeled under figures specific in either painting for reference and juxtaposition (Blake’s Pilgrims and Selected Figures and The Pilgrims Compared).

What struck me most was the end selection of critical comments and reviews contemporary to the time, chronicling excerpts of reception regarding both paintings. These offer avenues of research that focus more on sociological and political viewpoints on aesthetics in the English art scene, some of which were involved in museum curation. Also to note is the layered consultation of primary, secondary and tertiary sources apparent through the overview.

“Illuminated Painting by Joseph Viscomi”: http://www.blakearchive.org/exhibit/illuminatedprinting

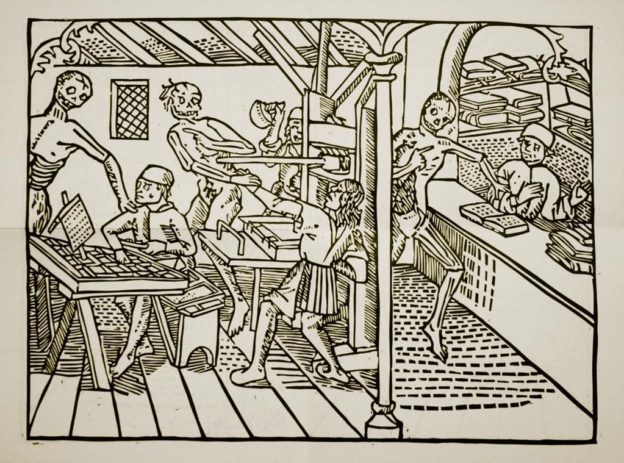

Exemplifying a more technical analysis on processes and technique, “Illuminated Painting by Joseph Viscomi” is an exhibition that takes on the agenda of textual criticism by delving into material and the advancements of printing technology in their effect on Blake and his Romantic approach.

Through adaptation and arguably innovation, Blake developed his own methodology reminiscent of all his interests (painting, poetry and printmaking) and so the exhibition carries from the beginnings of the plate to the developed book. Specifically, I enjoyed and wished for more small interjections regarding other participants like that of his wife in his process, whose collaborative labors are often hidden. The same can be said for the economic and labor-specific realities introduced in the conclusion and more assumptive in the reader’s knowledge on literature and book distribution in this period.

Blog:

https://blog.blakearchive.org/

David Erdman’s publication, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, on the collection:

http://erdman.blakearchive.org/

Further Research:

http://www.blakearchive.org/staticpage/generalbib

For behind-the-scenes and modern introspective, the site offers tabs on the front page labeled Blog, Erdman, and further down Resources for Further Research. These overviews on the site’s construction, its repository of associated works, and collection aid in navigating the narrative woven through The William Blake Archive. Even more so does it encourage others to participate and actively add upon the self-acknowledged incompleteness of the research and archive.

While David Erdman’s The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake veers a bit on the daunting side for newly introduced individuals on this academia, the site itself establishes enough to make this more packed interpretation and contained edition accessible for those wanting to focus their own scope or questions regarding William Blake. While this edition is made accessible, one thing to note is its newest revision is in 1988 and omits electronically some of the content in the physical copy. It thus remains apparent that archival itself retains obsolescence as a persistent question in doing so.

Issue Archive: http://bq.blakearchive.org/

Current Issues:

https://blakequarterly.org/index.php/blake

The site also archives modern academia and research that preceded the site in its digital format. Peer reviewed articles and established criteria help to foster a community with this particular interest in Blake, but at the same time also demonstrate flexibility as it adapts to the expanding definition of academia. The stakes and responsibility that come from this establishment of “trust” and reputation then adhere to much of the acceptance and choice of showcased research and articles.

What’s New?

http://www.blakearchive.org/staticpage/update

The mindfulness apparent in all of the features in the William Blake archive demonstrate that the archive as a work in progress is still cycling through becoming more and more efficient. While this strive for efficiency does not always allow for success, this digital project highlights the value of error and process. While not everything can be covered or touched upon, digital impermanence paves the way much like academia is now doing—questioning and delving into the continuous remediation of information.