In Andrew Robinson’s “Writing Systems”, he suggests that it does not seem likely that writing evolved from the counting system of clay ‘tokens’ (which served as an extension of human memory already in the late 4th millennium BC) – despite of the fact that many hold the belief that writing grew out of the counting system; rather, the emergence of writing was accompanied by the ‘tokens [1].

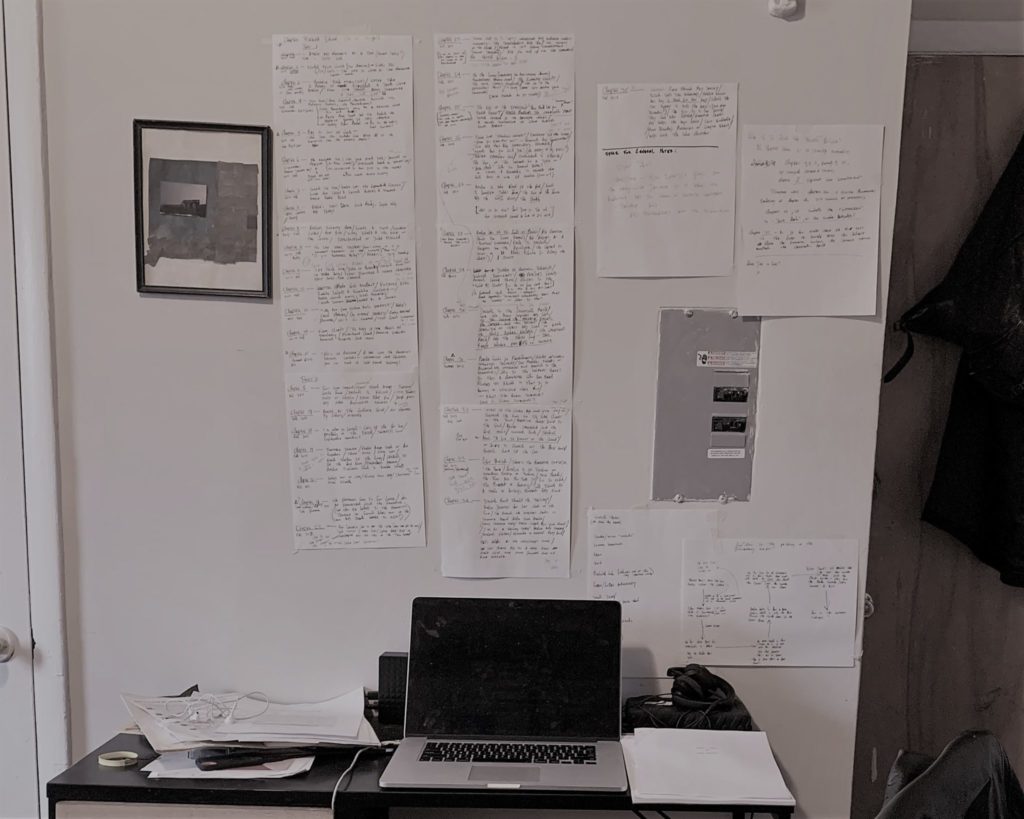

Jerry Eugene Pournelle’s cost-benefit analysis of writing, as recorded by Kirschenbaum in the first history of word processing, not only evokes the primeval conditions that give rise to writing but also suggests the new definition of writing in a digital age [2]. To Pournelle writing equals to, in his own words, “the business of making a living” [2]. What his motto “writing is hard work” reflects is not the divinity of the writing process but “the actual labor of being an author”, the idea that “anyone can learn to do it” and the idea that one’s writing is one’s work.

Even though modern technologies, such as microcomputer or the word processor, free human beings from the tedious aspect of editing and rewriting, the real relationship between writing and society still does not change that much; it is only the awareness of the divine (but not necessarily religious) origin of writing is lost. To twist a bit what William Blake wrote to his reader in the preface to the first chapter of his longest illuminated book Jerusalem, “[Human civilizations] are destroy’d or flourish, in proportion as their Poetry, Painting, and Music are destroy’d or flourish. The Primeval State of Man was Wisdom, Art, and Science” [3].

Reference

[1] M. F. Suarez and H. R. Woudhuysen, Eds., The book: a global history, First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

[2] M. G. Kirschenbaum, Track changes: a literary history of word processing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

[3] “To the Public. Selections from ‘Jerusalem’. William Blake. 1908. The Poetical Works.” [Online]. Available: https://www.bartleby.com/235/304.html. [Accessed: 25-Feb-2020].