How have material changes effected the way we read? As one of the events that gave rise to modern times, two perspectives on the development of printing technology can be roughly summarized; the position that mass production of books has resulted in the democratization of knowledge or that the rule of power was strengthened through the means of the dissemination of knowledge. I would like to discuss the change in the way we read as a result of the critical insist, which is closed to the second one, that the development and diffusion of printing technology was possible by particularly meeting the contemporary context of capitalism.

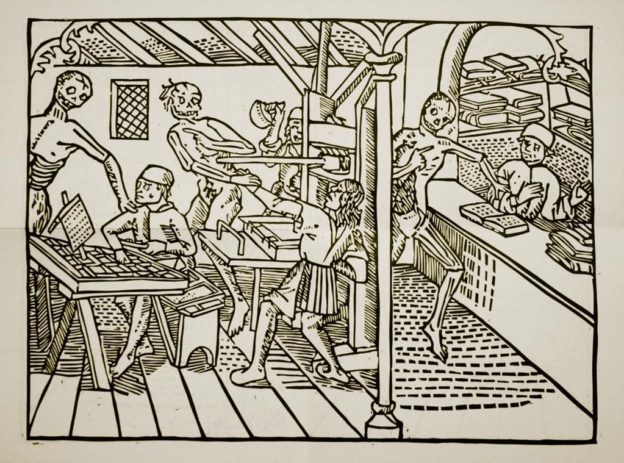

Initially, Gutenberg’s famous ‘42-line Bible’ was widely produced by theologians for the religious purpose of distributing the Bible. Historically, however, it has only been able to continue and spread as the demands have been met within the system of private markets, at the same time, the abundance of supplies and the consumer-oriented societal ambience due to the declining population after the Black Death. In addition, when it was regarded that the Reformation had risen by the fact that Martin Luther’s ‘Ninety-five Theses’ were quickly printed and distributed, it is important to note that the Reformation, which emphasized ‘individuals’ who can directly face God, led to Calvin’s Protestant outbreak and was very friendly with the capitalist spirit. In short, printing technology was able to develop and disseminate in the process of forming the capitalist structure that was born at the time, and was also a catalyst for opening a new epoch.

By being part of the capitalist system, printing technology has made it possible for everyone to be subjective readers, but at the same time it makes us all consumers of equally mass-produced knowledge. Thus, the material change of printing technology does not simply change the way we read, but the content what we read. In the form of printing, knowledge exists as a commodity, and texts that do not conform to the logic of the market do not survive or cannot enter at all. Therefore, in this macro capitalist logic we might also ask: How do we change what we read?